The Old-Timey New Zealand T20 XI

Selecting an all-time New Zealand T20 XI from players who never played T20 cricket.

One of the great shames of cricket is that it has only existed for about 150 years, and not 1,500, or even 15,000. Accordingly, we have no idea how some of history’s preeminent figures would have performed at our great game. Could Genghis Khan face left arm wrist-spin? Was Jesus a compulsive hooker? What were Plato’s thoughts on the morality of the Mankad? Would Mao Zedong approve of BazBall? Sadly, these and similar unanswerable questions will forever plague historians.

An even greater tragedy is that, after inventing cricket, it took us another ~125 years of sitting on our thumbs to then invent T20 cricket. As such, not only do we not know whether Charles Darwin would have favoured backward point or midwicket—we don’t even know how some people who actually played cricket would have performed in the shortest format.

Frankly, that is unacceptable to me, so, with the almighty power of vibes and imagination, I’ve dreamed up my ideal Old-Timey New Zealand T20 XI. The basic premise is that I’ve used stats and informed guesswork to predict how these guys would have performed in T20 cricket, offering my opinion on the closest equivalent modern comparisons. There are no hard and fast criteria, only that you can’t have played T20 cricket in your prime (meaning the likes of Cairns, Harris, and McMillan, who played a bit at the end of their careers once they were past their best, qualify).

The idea for this article has been heavily inspired by this excellent article from Jarrod Kimber over at Good Areas, as well as this subsequent video/podcast. I highly recommend reading/viewing both, and just generally subscribing to Good Areas and consuming all the excellent content Jarrod produces. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the best analytical cricket content on the market today, and the major impetus for me starting this blog. So, all credit to the Good Areas team for dreaming up this awesome format. If anyone from there happens to be reading this, I hope it’s okay that I’ve been ‘inspired’ by it, and I love what you do!

Anyway, onto the XI:

Unselected: Martin Crowe—but only because he is busy captaining, coaching, and organising an all-time Cricket Max side to face this team.

The Opening Pair

1. Chris Cairns

2. Ian Smith (WK)

Chris Cairns is the first name on this teamsheet, and the salivating at the thought of him playing T20 cricket partially inspired this article. While Cairns did ultimately play two T20Is and 14 T20s total, these were all between 2005 and 2008, when Cairns was 35-38. In fact, 9 of Cairns’ 14 T20s came in 2008 for Nottinghamshire, by which point he was 38 and had been retired from international cricket for two years. Suffice it to say, take Cairns’ existing T20 numbers with a grain of salt. Peak Chris Cairns would have been an utter force of nature in T20 cricket, almost purpose-built for the game. I can see him opening the batting and dominating the fielding restrictions in the powerplay, while also causing havoc with the new ball and offering some skills at the death, too (though, with Hadlee and Collinge, these shouldn’t be called on too often). For a modern comparison, think Mitch Marsh with better bowling.

Joining Cairns at the top of the order will be the familiar, calming voice of Ian ‘Barest of Margins’ Smith. I went back and forth quite a bit trying to decide whether Smithy deserved this spot or whether Mark Greatbatch could take the gloves and reprise his pinch-hitting role from the 1992 World Cup. Ultimately, I favoured Smithy’s superior glovework and in-built relationship with Paddles. It’s not just that Smith is a superior wicketkeeper; he was also a real go-er with the bat for his era, as an ODI strike rate of 99.43 attests to. Despite debuting in 1980, that means Smith has the 55th-best ODI strike rate of all time—remarkable, given how thoroughly the game has changed in the interim. It’s barely still the same sport, but there’s Smithy, rubbing shoulders with Shubman Gill and Sanju Samson. Lance Cairns, who we’ll get to in a moment, is the only person above Smith on the list who debuted before him. As such, Smith would be given the ultimate licence to go hell-for-leather from ball one and get the team off to a flyer. For a modern comparison, I would want to deploy him in a role similar to Sunil Narine (the batter) or a Finn Allen/Jake Fraser-McGurk type: swing at everything. With batting down to Patel at 9, I wouldn’t be too concerned if he didn’t come off, because when he does, it will be match-winning.

The Middle Order

3. Nathan Astle

4. Craig McMillan

5. John Reid (c)

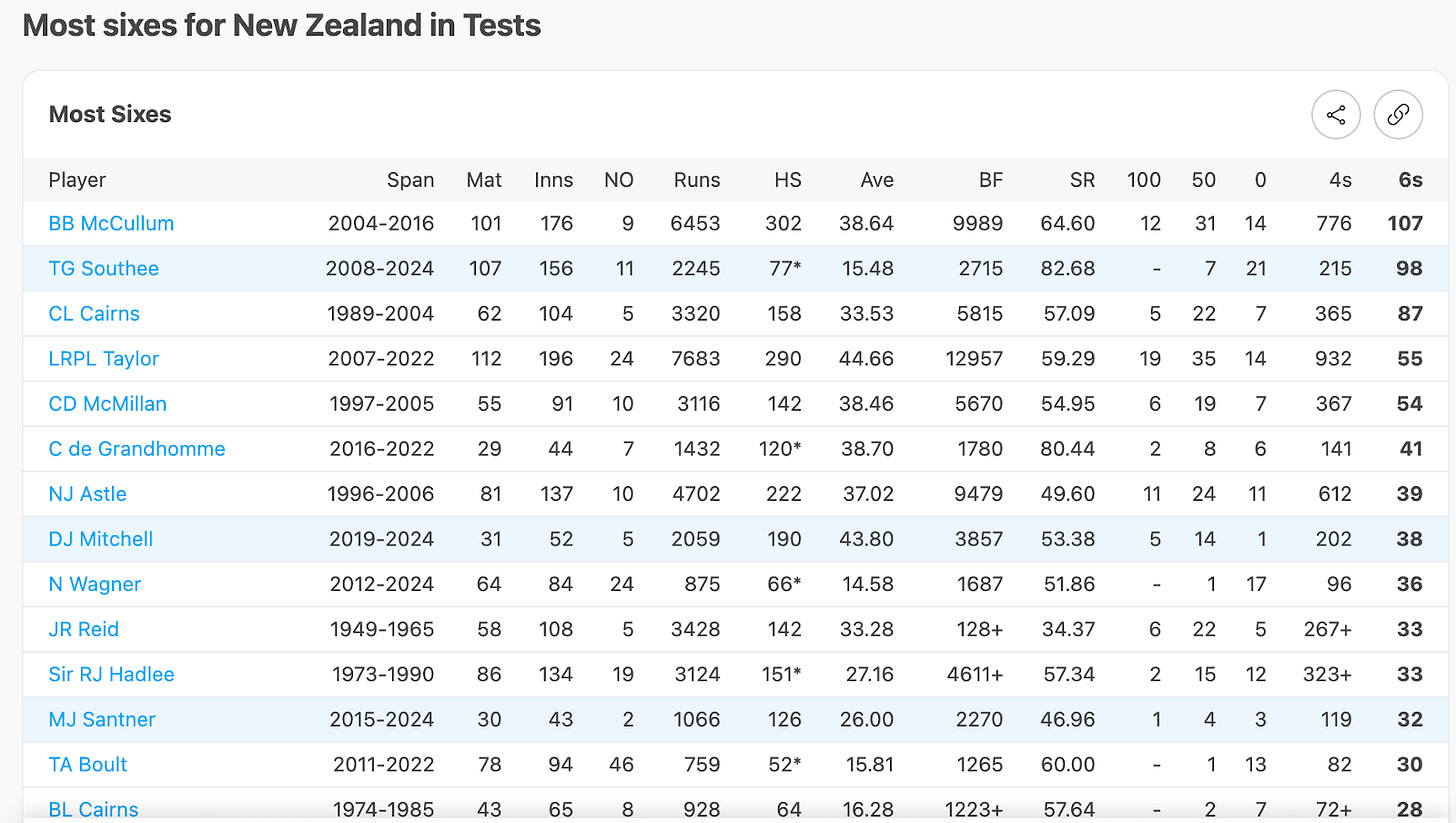

Reflecting on Astle’s 222 (168), as I often do, was another large part of the impetus for creating this team. Yeah, I reckon the guy who still owns the record for the fastest 200 in Test cricket, and can also offer some part-time overs if need be, would have figured T20 cricket out. If you need more justification, Astle has also hit the 7th most Test sixes and the 5th most ODI sixes for New Zealand. Like Cairns, Astle did play 22 T20s at the end of his career, averaging a respectable 27.25 and striking at 115.5. However, these all came when Astle was 34-36, and it’s a mouth-watering prospect to imagine what he might have achieved in the format in his prime. Given how much both love to cut the ball, Travis Head might be an apt modern comparison.

As an aside, isn’t it a neat quirk that the men who have scored the two fastest Test double hundreds, Nathan Astle and Ben Stokes, were both born in Christchurch? Small world.

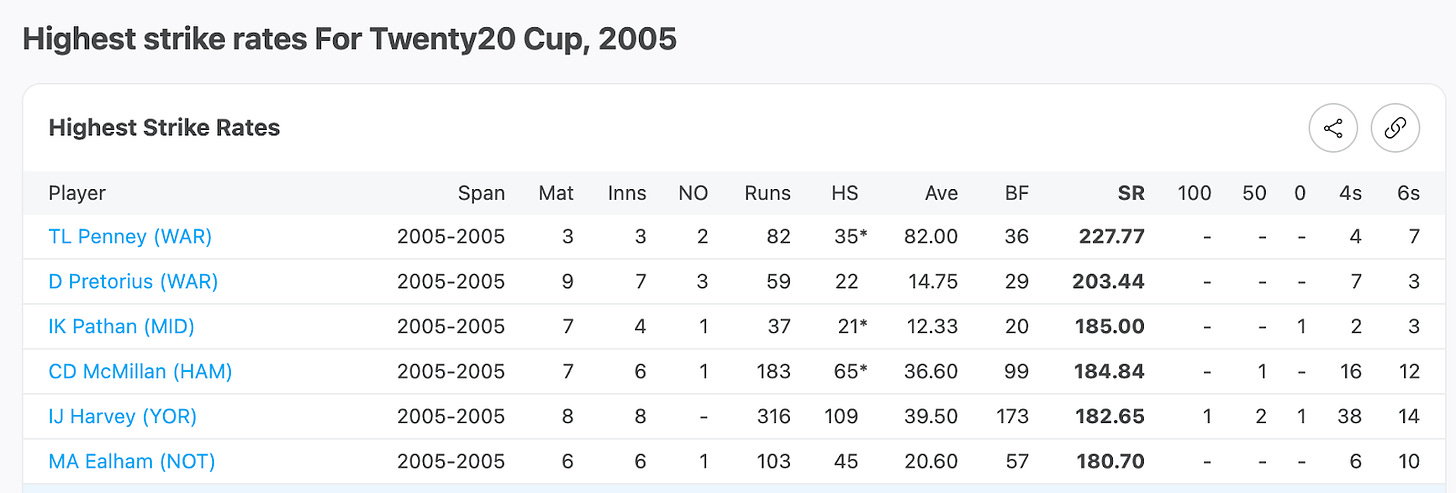

Joining Astle in the middle order is another batter from a similar era, Craig McMillan. Like Astle and Cairns, McMillan played 27 T20s at the back end of his career, with all of them coming by the time McMillan was already 30, and a quarter coming once he was 34. However, unlike Astle and Cairns, McMillan clocked T20 cricket from the get-go, striking at 148.6 domestically and 159.8 from eight T20Is. That would still be rapid these days, let alone back then. What’s more, McMillan played the 2005 Blast (or whatever it was called back then) for Hampshire, averaging 36.36 and striking at 184.84—the highest strike rate of any batter to score at least 100 runs that year. Only Ian Harvey, who struck at 182.65, was in McMillan’s league. Add in McMillan’s bowling and the fact that he has hit the 5th most Test sixes and 6th most ODI sixes for New Zealand, and this selection was a complete no-brainer. For a modern comparison, think someone like SKY or Sanju Samson.

Rounding out the middle order and captaining the side, we have the legend himself, John Reid. There’s not a lot I can add here that Reid’s Cricinfo bio doesn’t already cover: “A super allrounder, John Reid was born a generation too soon, for he retired in 1965 before one-day international matches were started. Reid would have been a one-day team on his own - a batsman with thunderous strokes, a rapacious fielder especially at gully or cover, a bowler of what became known as right-arm bursters which ranged from modest off-cutters to snarling bouncers. Reid also fitted in some stand-in wicketkeeping.” My only correction is that he was actually born two generations too soon, because if they reckon Reid would have been good at ODI cricket, I can only dream of the bidding wars he’d have started in the T20 game. As a massive, hulking bowler and hard-hitting middle-order batter, would it be too cheeky to compare Reid to Andre Russell?

The All-Rounders

6. Chris Harris

7. Lance Cairns

8. Richard Hadlee

9. Dipak Patel

If John Reid hadn’t existed (I shudder to think), Chris Harris would have been the captain of this side. As an outstanding ODI finisher, an incredibly miserly bowler, and one of the best fielders you’ll ever see, it’s almost as though Zinzan was purpose-built for T20 cricket before it even existed. Harris is another who played 27 T20s at the tail end of his career, between the ages of 37 and 41. Even at that age, he still averaged 70.66 while striking at 120. Yeah, not bad. I reckon he might have gone alright in his prime. My only slight concern is that Harris is more of a nudger and a nurdler than a noted six hitter, though he has still hit the 15th most for NZ in ODI cricket, and with Reid and Cairns either side of him, clearing the rope shouldn’t be too big of an issue. As a batter, I think he’d be a KL Rahul-type: a high-averaging anchor capable of cycling through the gears when needed, while his bowling is roughly equivalent to a Marcus Stoinis-type, as a handy part-time option, but not someone to rely on to bowl four overs every game.

At number seven, yes, I think the guy who famously hit a one-handed six at the MCG would have been quite good at T20 cricket. Hot take, I know. Lance Cairns debuted for New Zealand in 1974 and still managed to strike at 104.88 in ODI cricket—practically unheard of for the era. That’s still good for the 33rd best ODI strike rate of all time, with 31 of the players ranked ahead of Cairns on that list debuting in the 2000s. Amid all that, it’s probably slightly overlooked that Cairns’ primary skill was his bowling, taking 473 first-class wickets at 26.52. I’m gonna go out on a limb and say he’d have been pretty handy in the shortest format. Think a Rashid Khan-type chaotic hitter and destructive finisher, and a Shardul Thakur-esque bowler.

Obviously, Richard Hadlee makes the team. I won’t waste your time or mine by explaining why. He was very, very good at cricket, old Paddles. For a modern comparison, I predict he would have been exactly as good as Sir Richard Hadlee (high praise indeed).

Rounding out the all-rounders, we have Dipak Patel, of opening the bowling in the 1992 World Cup fame. If you’re wondering why I classed him as an all-rounder, he scored 26 first-class hundreds and averaged nearly 30. But, of course, Patel is primarily in the team for his bowling, and with spinners bowling in the powerplay being all the rage in T20 cricket these days, who better to fill that role than the original white ball powerplay spinner? With an ODI economy of 4.17 and a first-class mark of 2.73, I predict Dipak would have been extremely tricky to hit off the square, in a similar mold to Mujeeb Ur Rahman in the powerplay, but with Adil Rashid-level batting. Patel might not have quite the same bag of tricks as Mujeeb, though I bet if he were playing these days, he’d have picked a few up.

The Bowlers

10. Richard Collinge

11. Darryl Tuffey

Onto the bowlers, and we have Richard Collinge at number 10. If you don’t know very much about Collinge, let me share the only two relevant facts:

Collinge was 6 feet 5 inches tall.

Collinge bowled with his left arm.

That’s it. Teams would have absolutely tripped over themselves to secure his services. If you’d like to know a little bit more, Collinge took 524 first-class wickets at 24.4. If you’d like to know even more than that, Collinge’s ODI economy of 3.34 would be the 7th best of all time, just behind Michael Holding, but he falls slightly short of the 1,000 ball qualifying mark (859). Think of Mitchell Starc or Spencer Johnson, for a modern comparison.

Rounding out the team at number 11 is Darryl Tuffey. This might seem a slightly curious selection, at first, but I have a very specific reason for making it: first over wickets. As a bowling team, there is no more valuable commodity in T20 cricket than powerplay wickets, and the earlier, the better, making first over wickets the ultimate prize. Tuffey was a master at this particular skill.

It’s a difficult, niche thing to find precise stats on (just my sweet spot), but this New Zealand Herald article reckons Tuffey took 18 first-over victims in international cricket, counting among them Sehwag, Shahid Afridi, and Jayasuria. If you can overcome those three swinging wildly at you in the first over of an ODI, you can handle the Finn Allens and Travis Heads of the world doing it in the first over of a T20. The modern comparison here is pretty straightforward: I’d want Tuffey to fill a similar role as Trent Boult has in the IPL, where he has taken a record 30 first-over wickets. With this team stacked for bowling options, you could bowl Tuffey for two or three overs in the powerplay, and then not have to return to him at the death.

For balance, I am also obliged to remind you that Tuffey also once bowled this, the worst first over in ODI history.

The Bench

Ewen Chatfield, Glenn Turner, John Bracewell, and Mark Greatbatch.

It pained me to leave Ewen Chatfield, who still has the 17th best economy rate ever in ODI cricket, just ahead of Dennis Lillee, out of the main XI, but compromises had to be made. To be fair, with Harris, McMillan, and Astle, we’re well stocked for dibbly-dobblers. If the wicket offered any seam or spice, you’d swap Chatfield and Patel.

Like Hadlee, I won’t waste your time or mine by explaining the Turner selection. He was an incredible batter and would have figured out any format, given enough opportunity. You could stick him anywhere from 1-6 and he’d make it work, making him a perfect backup batter for this squad, which is incredibly disrespectful as the most naturally talented batter in this squad, but hey, that’s T20 cricket (just ask Kane).

As a miserly offie who could hit the ball hard down the order, John Bracewell is another who almost feels purpose-built for T20 cricket, before it even existed. He’s essentially the proto-Mitchell Santner, or, well, Michael Bracewell. You’d swap him in for one of the seamers if the pitch offered any turn.

Finally, I spent a long time going back and forth between Smithy and Greatbatch at the top of the order. Ultimately, Smithy’s superior keeping and excellent strike rate won out, but I could have just as easily deployed Greatbatch at the top of the order in a similar pinch-hitting role to the one he played in the 1992 World Cup, where he scored 313 runs at 44.7 with a strike rate of 87.9. Of that tournament's 25 highest run scorers, only Martin Crowe and Inzamam-ul-Haq had higher strike rates than Greatbatch. He’s the backup keeper if Smithy goes down and also the spare attacking batter, whereas Turner is more the spare anchor.

The Coach

As the story goes, John Wright was the person who discovered Jasprit Bumrah. To hear him tell it:

“I was watching [the] back end of a game when Mumbai were playing Gujarat. Mumbai were easily going to win, but there was this kid with a short run-up, and he bowled two overs of yorkers. He really interested me because I think sometimes when you’re looking at players–and you see this in other sports–you look for something a bit different or a bit special. What he had was pace, and the other thing was he was trying to bowl 12 yorkers on the trot, and he did it quite well. I had a chat with Parthiv Patel, who was the captain of Gujarat and was in the Indian team I coached. I said, ‘Well, who’s that kid?’, he said, ‘Oh, that’s Boom’, I replied, ‘Who is Boom?’, and says, ‘It’s Jasprit, Jasprit Bumrah and he’s 18 years of age’. So, we signed him overnight and he joined us (Mumbai Indians). He was very young, so I asked him to bowl to Sachin Tendulkar. It turned out to be music to my ears because at the end of the net, Sachin came up to me and said, ‘John, that kid is hard to pick up’, so that’s how it all started.”

Enough said. Yes, I would quite like to have those sorts of talent identification skills on my team, thank you very much, and I was trying to find a way to shoehorn Wright into the side anyway.

Team Tactics Talk

With batting down to Patel at number nine (and even Collinge and Tuffey both scored Test fifties), the instructions will be to go hard from ball one, with Smithy in particular given a Finn Allen-esque free license in the powerplay. I’d ask Cairns to bat more like Gayle, a notorious slow starter, knowing how destructive he could be if he gets set and faces enough balls.

In the middle order, while I’ve listed a set order, I’d want to be flexible. On trickier wickets, I’d promote Harris as almost a ‘floating anchor’, while in games where 200+ is par, I’d look at promoting the likes of Lance Cairns up the order and telling him to go wild. Reid and Harris, the two left-handers among the top six, would also be tactically deployed to maximise left-right partnerships and disrupt opposition bowling matchups. My one concern is the lack of a clear spin hitter in the middle order, and I would focus on developing Astle or McMillan in this role.

On the bowling side of things, we’re utterly flush with options, with everyone except for Smith able to roll their arms over. Except for in the most dire of scenarios or against the best possible matchups, I’d want Astle, McMillan, and Harris bowling as little as possible in this team.

Tuffey and Hadlee would, obviously, take the new ball with Patel also being deployed in the powerplay, while the towering Collinge would be used as an enforcer throughout the middle overs. Depending on the specific matchups and opposition, you can then split the remaining overs between the two Cairns’ and Reid as required, and select your death options based on who’s bowling well that day, with Bracewell coming into the XI on spinning wickets.

Lastly, I’d love to see others have a go at their version of this team (or the equivalent for your national team), so please, share them in the comments!

Thanks for reading! Like my work? A lot of effort and research goes into pieces like these, so please consider supporting me via a paid subscription or Buy Me A Coffee. For more info on how your support helps me produce this work and what your contributions go towards, see my About Page!

Like my work, but not that much? Fair enough! If you still want to support me, the best thing you can do is share this article far and wide: whether that’s with friends and family, teammates at your local club, on Reddit, or in your obscure cricketing discord server, I cannot emphasise enough how helpful every single share is.

Just keen to continue reading about cricket? No worries! If you liked this article, I think you might also enjoy:

Fantastic stuff! I’m not sure I could put together a better old-timey team other than finding a place for Crowe, but it does make me think that the 1992 side would’ve made a damn good T20 side, especially with Greatbatch opening.

In fact, they effectively played a T20 against Zimbabwe, with Crowe dominating (74 off 43).